Artist Statement

October 1, 2025 Masahiro Hiroike

日本語版はこちらです

Overview

Hiroike is a Japanese photographer born in 1962. His career as a photographer began in earnest in 2020 when he was selected as a finalist in the Professional competition of the Sony World Photography Awards (SWPA), one of the world's largest photo contests. Since then, he has continually received awards in international competitions and currently serves as a jury member for some of them. Furthermore, museum-hosted solo exhibitions of his work have been held in Japan and Poland, and in 2024, he debuted as an artist in the 90-year-old "Yamakei Calendar."

Since childhood, he has had a passion for nature, enjoying outdoor hobbies such as stream fishing, cycling, and mountain climbing. After encountering early computers at the Hiroshima University Faculty of Engineering, he worked as a systems engineer for over 30 years, involved in the development of industrial robots, CAD, and Web systems. It was the development of numerous photo display programs during this time that eventually led him to pursue serious photography. He expresses the unique nature, landscapes, and culture of Japan through his photography, driven by a deep reverence for nature.

His work is fundamentally influenced by Japanese paintings like Suibokuga (ink wash painting), breathing life into Japanese aesthetic concepts such as Utsuroi (transition/change), Wabi (austere simplicity), and Sabi (faded elegance). From an engineer's perspective, he also engages in a technical and philosophical exploration of the questions: "What is a photograph?" and "What is beauty?"

As a new form of expression, he is studying the relationship between time and photography, regarding photography as "a device that transforms four-dimensional space (three-dimensional space + time) into a two-dimensional plane." He is also utilizing the chance moments created by the movements of living creatures and ICM (Intentional Camera Movement) to reconstruct "Digital Photography Surrealism" by taking advantage of the characteristics of digital cameras. He is also pioneering "Action Photography," which is "photography that draws."

He is also committed to the photograph as a physical object. Beyond high-definition shooting, he personally undertakes "printing and framing," processes typically entrusted to specialists. He has installed large-format printers and panel-mounting machines at home to produce 2m x 1m large-format prints and conduct Alpolic processing (panel mounting using aluminum composite board) himself, developing custom-designed aluminum frames in addition to traditional wooden ones.

Prologue

Hiroike was born and raised in 1962 in the nature-rich Tottori Prefecture, Japan. From an early age, he played in the mountains and rivers, developing a deep connection with nature through stream fishing, cycling, and mountain climbing. Through experiences where he faced danger, he developed a profound sense of reverence for nature. When building his home, he chose to construct a log house in a forest in Hokkaido, prioritizing his connection with nature in both his daily life and hobbies.

Encountering early computers at the Hiroshima University Faculty of Engineering, he became a systems engineer involved in the development of industrial robots and CAD, and acquired the "Special Information Processing Engineer" qualification, the highest national certification for system development at the time. After becoming independent at the age of 29, he focused on Web system development and design, including an achievement of winning second place in a nationwide website contest. His work on numerous photo display programs was the catalyst that led him to start taking photographs seriously.

Journey to a Photographer

Hiroike first began challenging major domestic photo contests. In 2015, he won awards at contests organized by Fujifilm and Nikkor, and secured the Grand Prix at the Olympus Open Photo Contest. This success prompted him to expand his activity to international photography communities, including National Geographic's "Your Shot," and to actively submit to overseas photo contests.

In 2020, he was awarded 2nd Place in the "Natural World & Wildlife" category of the Professional competition at the Sony World Photography Awards (SWPA), one of the world's largest photo contests. However, the global spread of COVID-19 led to the cancellation of most awards ceremonies and exhibitions. Nonetheless, the award garnered significant attention, resulting in numerous friend requests from overseas on his Facebook, where he is now connected with approximately 4,000 people across 109 countries.

One such connection was with Mr. Zibi, the president of the Lower Silesian Photographers Association in Poland, whom he met on Facebook. Mr. Zibi initially planned a photo exhibition for him in Poland in November 2020, but it was postponed due to the pandemic and finally held in May 2023.

With further successes in other international contests like "35AWARDS" in 2020, Hiroike decided to become a professional photographer. In 2021, with support from a Tottori Prefecture subsidy, he held a large-scale solo exhibition at the Yonago City Museum of Art.

In 2024 and 2025, he was selected as an artist for the 90-year-old Japanese established nature calendar, "Yamakei Calendar (Yama-to-Keikokusha)," recognizing him as a leading Japanese landscape photographer.

The Pursuit of Beauty

Through a diverse range of subjects—from natural landscapes and flora/fauna to abstract expressions—Hiroike pursues a consistent theme: the "Pursuit of Beauty." When he started his career as a photographer, he was driven by the pure desire to "take beautiful photographs." However, the underlying question, "What makes humans perceive something as 'beautiful' in the first place?" led the engineer in him towards a technical and philosophical exploration.

The feeling of "beauty" arises from the resonance between the inherent beauty of the subject and the observer's aesthetics (sense of beauty). This aesthetic sense is shaped by highly diverse and profound factors such as biological instinct, the environment one is born and raised in, personal experiences, and learned culture and history. Japan, in particular, possesses a unique sensibility that allows people to find beauty even in things that might initially seem unattractive. He has made this question—"What do people feel beauty in?"—a major theme as he continues his photographic work.

Japanese Aesthetics

Hiroike's origin lies in landscape photography. Against the backdrop of his deep connection with nature and his influence from Japanese painting such as Suibokuga, he uses the medium of photography to express Japan's rare nature, landscapes, and the culture born from them, all filtered through the distinct Japanese aesthetic senses of Utsuroi (transience/transition) and Wabi-Sabi (austere, faded elegance).

Japan is a long, narrow island nation with a globally rare complex topography formed by the sea, mountains, and rivers, distinct seasonal changes, and a varied climate. This rich natural environment offers beautiful scenery, clean water, and abundant food, but also poses risks to human life through disasters like floods and earthquakes. Since ancient times, the Japanese people have coexisted with nature, holding it in awe and reverence. From the belief in Yaoyorozu no Kami (eight million gods) dwelling in all things in the natural world, they cultivated the faith of Shinto. Concurrently, as symbolized by terms like Kachōfūgetsu (Beauties of Nature) and Setsugekka (Snow, Moon, and Flowers), they found "beauty" in nature itself.

The Japanese aesthetic tends to perceive elements such as "simplicity," "stillness," "harmony," "ambiguity," and "delicacy" as "beauty." Furthermore, they have found unique sensibilities toward the transition and change in nature, expressed as Mujō (impermanence), Mono no Aware (a pathos or deep feeling about things), Yūgen (profound subtle grace), Wabi, and Sabi. For the Japanese, nature is an object of worship and the source of their aesthetics, crystallizing in cultural arts like Suibokuga and other Japanese paintings, as well as crafts. This aesthetic sense is deeply rooted not only in food, housing, and lifestyle but also in corporate philosophy and social ethics. For the Japanese, divinity resides in the landscape, and their aesthetic sense encompasses spirituality.

Photography and Time

The Himebotaru (Luciola parvula, a small firefly) has been Hiroike's subject for over 10 years. He began photographing them, initially captivated by the beauty of the lights dancing in the night forest. Gradually, however, he began to feel that the Himebotaru photographs held a significant suggestion relating to the concept of "What is a photograph?"

The usual method for photographing Himebotaru is composite merging of multiple images based on lightness. However, Hiroike succeeded in capturing them in a single shot by carefully adjusting the time of shooting and the exposure time. Himebotaru begin flying after sunset as the darkness deepens. Hiroike sets the exposure time based on the background brightness, and this time gradually lengthens as the forest darkens: 5 seconds, 10 seconds, 20 seconds, 30 seconds, 1 minute, 2 minutes, and so on. Since the Himebotaru flash momentarily at regular intervals, like a camera flash, they appear in the photograph as a string of dots, or as tamaboke (ball bokeh) if they pass close to the lens. The important thing to note here is that the exposure time does not affect the brightness of the firefly light, but rather the number of dots and bokeh circles that appear in the photograph. In other words, the exposure time has a different meaning for the background and the light trails of the fireflies.

When the daguerreotype was first invented in France, photography required exposure times of several tens of minutes. Since then, film and cameras have continued to evolve to allow instantaneous shooting, now achieving exposure times of a few ten-thousandths of a second. Because of this, photography has come to be viewed as "a device that records a moment" or "a device that converts 3D space into 2D." However, we live in a four-dimensional world where time flows through 3D space. Therefore, photography can also be defined as "a device that converts four-dimensional space (3D spatial dimensions + time) into a two-dimensional plane." This time dimension carries a different meaning for each subject, and sometimes includes the movement of the camera itself. Adopting this perspective dramatically expands the possibilities of photography.

Digital Photography Surrealism

Through photographing the Himebotaru, Hiroike arrived at another important concept: "Surrealism." Himebotaru do not fly as the photographer intends; their light trails are entirely subject to chance. Consequently, he uses multiple cameras equipped with timer releases to take approximately 1,000 photos per night, continuing this nearly every day from early June to late July. The total number of shots exceeds 40,000 per season, yet he selects only 20 to 30 pieces as final artworks. At one point, the question arose, "Can a photograph taken by chance truly be called my work?" Through research, he encountered Surrealism, the century-old movement that placed chance at the core of art.

In October 1924, the French poet André Breton published the "Surrealist Manifesto," launching an art movement that sought to illuminate the reality perceived by humans with the new light of the subconscious, depicting a "surreality" that transcends the everyday. While this movement is known for paintings depicting "dreams," there also exist works based on forms and patterns created by chance, received through the artist's subconscious.

Photography is inherently a device that reflects reality. However, viewing photography as "a device that converts four-dimensional space (3D spatial dimensions + time) into a two-dimensional plane," Hiroike uses this time dimension to expand the range of "realist" photographic expression. Through dialogue with the randomness of the Himebotaru's light trails, and by maximizing the capabilities of the digital camera and incorporating contemporary research on the subconscious, which has become more scientific, he has advocated "Surrealism in digital photography."

Selecting intuitively from a Countless Number of Photographs Containing Chance

Digital cameras allow for taking an enormous number of shots, which was physically and economically impossible during the film era. Iintuitively Selecting a single image from thousands of chance-generated photographs, like those of the Himebotaru, is an act of finding one that resonates with his own subconscious sense, making the beauty of the unconscious visible.

Adjusting and Re-shooting Based on Chance-Containing Photographs

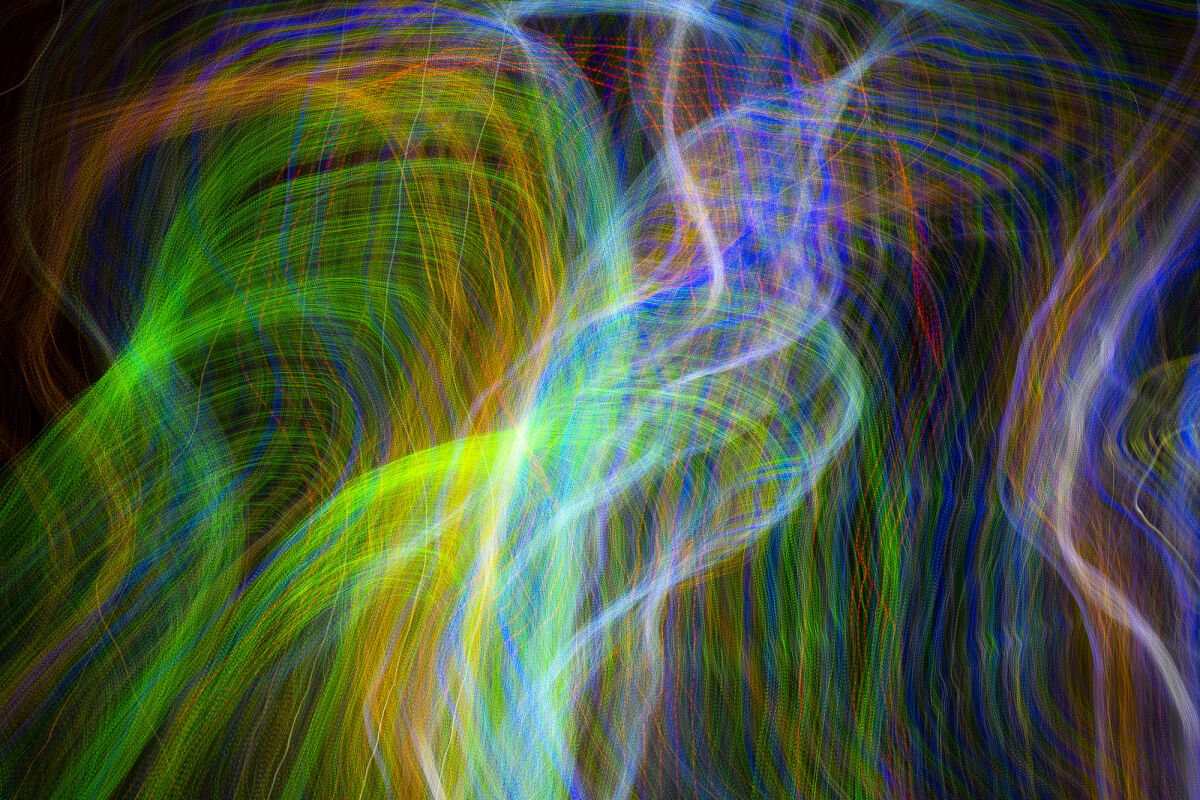

A key feature of digital cameras is the ability to immediately check the image on the spot. Hiroike photographs Japanese fireworks and Christmas lights using ICM (Intentional Camera Movement). ICM allows for creating chance-driven photographs by moving the camera freely, and for immediate review and adjustment for subsequent re-shoots. This is a creative process where the artist's intent reconstructs an image born out of chance. These approaches reinterpret the concept of chance pursued by the historical art movement of Surrealism, linking it to modern digital technology. Hiroike’s work is not merely a record of reality but an exploration of contemporary "surreality," born from the dialogue between chance, necessity, and the subconscious that transcends reason.

Action Photography

The painter Jackson Pollock created "Action Painting" as an extension of Surrealism. Hiroike's ICM (Intentional Camera Movement) works similarly revolve around "movement," evolving photography into an expressive form of "drawing." He named this approach "action photography" and advocated it.

With ICM, the light from fireworks and Christmas lights is stretched along the flow of time, and its changes can be recorded much like a seismograph. For example, the LEDs in Christmas lights flash at the AC frequency, but when photographed while moving the camera, the light trails appear as dotted lines. In the case of fireworks, the delicate splitting of small sparks and color changes are captured, with the light itself creating a unique matière (texture). Furthermore, as light energy and physical movement intersect and the complexity increases through synergy, forms suggesting the universe or living organisms emerge. Through the overlap of chance and necessity, movement and time, light and body, the photograph is no longer a mere record but is generated as a "surreal dream" that is drawn.

Exploring the Realm of High-Definition Expression

Hiroike's consistent theme is the “pursuit of beauty.” As evident in the existence of the “miniature painting” genre in art, he believes that “high definition” is one of the crucial elements of “beauty” in contemporary photography. Furthermore, Japan is a world-renowned powerhouse in cameras and printers, holding over 90% of the global digital camera market share and over 50% of the printer market share. Hiroike, who spent many years as a systems engineer developing slide show programs and other software, has always taken deep pride as a Japanese person in these photography-related technologies. Consequently, when he began his career as a photographer, he pursued “high-definition photography” more than anyone else.

Expanding Expression Through High Definition

Recent advancements in high-resolution digital cameras, image processing software, and large-format printers have made “high-definition large-format prints” possible, something previously unimaginable. Even at sizes exceeding B0 (1.5m x 1m), it is now possible to achieve such intricate detail that it cannot be discerned without a magnifying glass.

Hiroike works with B0 size and larger as his baseline, honing his skills in high-resolution photography, PC-based panorama stitching, and super-resolution techniques. This overwhelming resolution not only gives photographs new power but also enables new forms of expression previously impossible with conventional print sizes, such as “animals living within vast landscapes.” This is not merely an improvement in quality but an attempt to expand the realm of expression.

The Production Process as the Culmination of Engineering

Traditionally, Japanese photographers have outsourced large-format printing and framing to specialists. Large-format prints require “panel mounting,” which demands specialized tools and techniques, making it very costly. To exhibit primarily “high-definition large-format prints” at his photo exhibitions, Hiroike took on the challenge of “printing and framing” himself.

Leveraging his hobby of woodworking and experience in robot development, he remodeled his home garage into a print workshop. He installed a large-format printer capable of handling 44-inch media and a 1600mm-wide cold laminator there, enabling him to produce B0-size prints and perform Alpolic processing (mounting on aluminum composite panels). In addition to standard wooden frames, he has also developed his own custom-designed aluminum frames specifically for B0-size prints.

His photographic works represent the culmination of his respect for Japanese technology and his relentless pursuit of high definition, underpinned by engineering.